Providence Cyclodrome

This property is actually a tale of three things — competitive cycling, a football stadium, and the Providence Steamroller

images of this Property

-

-

-

-

-

![]()

-

![]()

Rare photo seen on Ebay of United Electric Railway Co., North Main Street -

![]()

Notice the sign for the Cyclodrome entrance on the side of the building (White Street) -

![]()

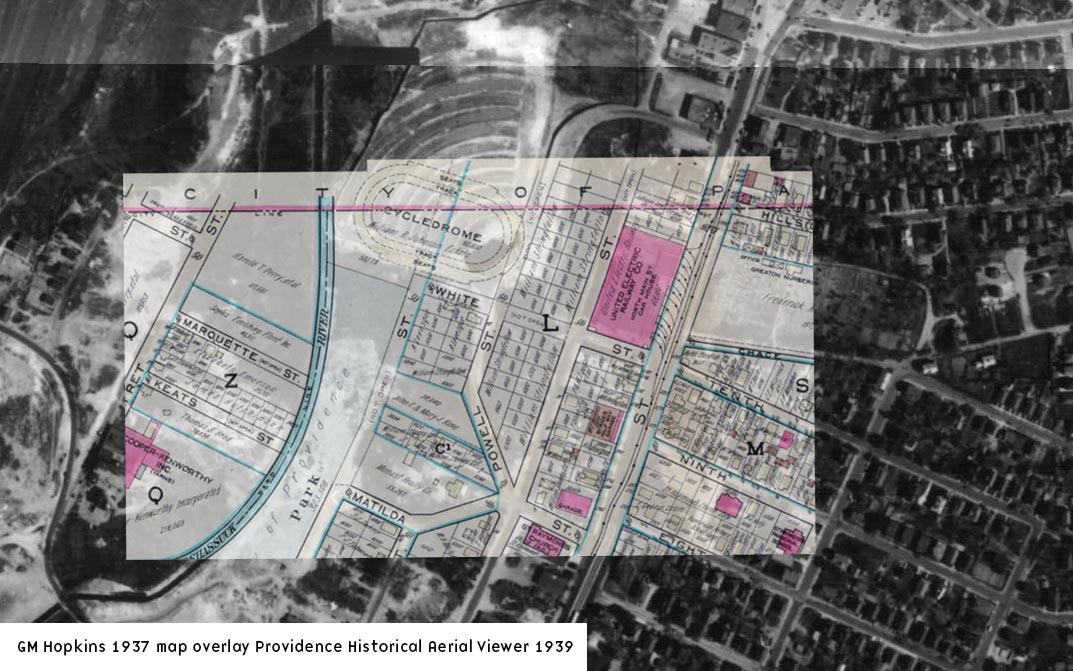

Map from 1937 shows the Cyclodrome in dashed lines, which we take to mean that it was in the process of being demolished -

![]()

The map is overlaid an aerial photograph from 1939 at 66% opacity -

![]()

The map is overlaid an aerial photograph from 1939 at 33% opacity

10 images: Press to view larger or scroll sideways to see more. Various sources. Playbill from AntiqueSportsShop.com, insurance map from HistoricMapWorks

About this Property

Quick History

In bullet points:

The Cyclodrome

- Opened on June 3, 1925, and considered a state-of-the-art facility, featuring a wooden five-lap track

- Designed to hold 13,000 fans, making it the largest bicycle track anywhere in the nation at the time

- Hard to be sure, but the theory is that the track was five laps to a mile, not five laps to a kilometer as most tracks today might be

- In 1937 the site was razed and one of the nation’s first drive-in movie theaters was built

A Football Stadium

- The Cyclodrome was an NFL Stadium for seven seasons — 1925-1933

- The field was inside the steeply banked track which cut sharply into the end zones and reduced them to just five yards in depth

- During games, temporary seating was permitted on the straight-away portion of the track, which was so close to the field that players, after being tackled, often found themselves in the stands

- In 1930 floodlights were installed at the stadium for night games

Providence Steamroller

- The Steam Roller was established in 1916 by members of the Providence Journal; sports-editor Charles Coppen and part-time sports-writer Pearce Johnson

- First team to play four regular-season games in six days

- First team to play a night game under floodlights — November 6, 1929 (at a different location than the Cyclodrome)

- The Steam Roller became the first New England team to win the NFL championship — 1928

Sources

We support and admire the Weird Island podcast!

Visit on the web: Weird Island Episode 59: Cycledrome and the First New England NFL Champions

Essay

Providence’s Lost Stadium: The Providence Cyclodrome And The City’s Sporting Past

Prepared by Leah Nahmias for a Historic Preservation class, December 12, 2007

Eighty years ago, the most exciting sports in New England were not found in Foxboro or the Boston Garden. At that time, some of the nation’s best racing and football was a short trolley ride from downtown Providence. In the late 1920s, the Providence Cyclodrome regularly packed in 10,000-plus fans to watch touring professional cyclists, cheer on homegrown amateur and semi-pro “anklers,” or to witness the crushing hurly-burly excitement provided by the city’s own professional football team. Tuesdays and Fridays were standing-room only at the ‘Drome; one Sunday 13,000 fans were packed like sardines to watch the Steam Roller roll over the visiting New York Giants. The Cyclodrome was one of the sporting world’s hottest tickets and one of the city’s brightest jewels. Yet today the building is gone, no marker notes its place, and loyalties have moved north to Massachusetts, leaving the city bereft of homegrown loyalties. Thus begins the search for the Cyclodrome, Providence’s lost stadium.

Since it was torn down so long ago, well before Providence’s preservation movement started, there are no known articles on its history. One of the biggest challenges of this project was tracking sources that described the structure or the atmosphere inside it. Peter Laudati, one of the original owners of the Steam Roller, collected a scrapbook of clippings about the team. His scrapbook is deposited at the Rhode Island Historical Society and in it one can find passing references to the structure. Local football historian Pearce B. Johnson also wrote extensively and self-published his research; many of his passing references to the Cyclodrome helped to reconstruct what the atmosphere and playing conditions for the Steam Roller were. Whenever I could find precise dates in Laudati or Johnson’s materials, I then searched in the Providence Journal’s microfilmed archives. This resulted in a very uneven and hardly exhaustive search for descriptions of the site’s use.

When the Cyclodrome opened on June 3, 1925, it was considered a state-of-the-art facility. It was designed to hold 13,000 fans, making it the largest bicycle track anywhere in the nation at the time. Some reports claimed it was the largest track anywhere in the world. On opening day, however, the stadium was only able to accommodate 9,000 onlookers. Construction delays due to heavy rain had caused the opening date to be pushed back several days from its scheduled Memorial Day Weekend premiere. That 9,000 fans gathered on a Tuesday night to witness the stadium’s christening, however, indicates that the Cyclodrome was an eagerly anticipated civic icon.

The Cyclodrome featured a wooden five-lap track. Programs reminded visitors to kindly step on all matches, cigars, and cigarettes to prevent fire from breaking out and destroying the structure. That so many of the patrons smoked hearkens to another era, certainly, but probably also indicates that most of the fans who attended races were men. Though flappers defied convention and smoked publicly in the 1920s, this was still not common practice for women of the time.

Determining the length of the track has been somewhat difficult. It is unclear if “five-lap track” means that it took five laps to complete a mile, a kilometer, or some other distance. According to a cyclist at the Providence Bicycle shop, tracks today are measured by kilometers. If this held true for 1925 a track that took five laps to complete one kilometer (a 200 meter loop) would be rather small by today’s standards. However, the size of the track drew a lot of attention in contemporary reports. One report called it a “mammoth bowl,” and another report tells of visiting cyclists taking practice laps around the track to acquaint themselves with its unfamiliar proportions. The major race on opening night was a 30-mile race. These several facts combined lead one to speculate that the “five-lap” size actually meant that the distances were measured in miles and that the “five-lap” size meant it took five turns around the track to complete a mile.

Opening day was described as a very exciting event for the city, and apparently one that had been anticipated for some time. Thousands of curious onlookers had reportedly visited the site while it was under construction in the spring of 1925. This was the scene on the Tuesday night when the track finally opened:

It was a big night on North main street last night — the biggest that thoroughfare has seen in years. The Cyclodrome opened, and there was bicycle racing, passing of floral tributes, band concert, singing and excitement galore. More than 9000 persons from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and these plantations gathered to give “the largest bicycle track in America” a rousing send-off. It was a grand and glorious opening and everybody was happy because the racing was of high quality, marked with close finishes and fairly sizzling with brushes. The night passed all too quickly, and the classic of the evening, the motor-paced race, was over before the crowd realized that a great card of sport had consumed three hours.

Although Mayor Joseph H. Gainer of Providence did not attend opening night ceremonies, his representative and “ardent fan” John O’Connell did. One can all but hear civic pride bursting from him and every other resident in attendance when he welcomed them to “the biggest and finest bicycle track in the world.” Interestingly, O’Connell made sure to thank the “public-spirited men” who had financed the track. Clearly the Cyclodrome put Providence on the map in some circles, and the men who made it happen were considered local heroes. Gainer’s administration is noted for the improvements made to the city’s infrastructure during his tenure. These included developing the Port of Providence, improving the public school system, improving the highway system and passing zoning restrictions to encourage commercial development. Given Gainer’s emphasis on making Providence a competitive modern city, it is not surprising that the Cyclodrome was hailed as a great achievement and its builders as civic role models.

Although his name was not used in connection with the Cyclodrome in any of the contemporary newspaper accounts, the chief financier and owner of the building was Peter Laudati, a prominent Providence real estate developer. Laudati was an ardent promoter of sports ventures; in addition to the Cyclodrome he built Providence’s Kinsley Park, home of the Providence Grays baseball team in the 1930s. He was instrumental in bringing Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig to play an exhibition game at that park. Laudati was also the part-owner of the Providence Steam Roller NFL franchise.

Cyclodrome patrons were regularly treated to contests on Tuesday and Friday nights. Incandescent lighting made evening matches possible; “entrances, roads, and park” were lit so brightly that “night [was] changed into day.” In 1930, permanent floodlights were installed, the first such lights to be installed in the nation. Each evening featured a series of professional and amateur events, including single racers, sprints, tandem-biking, and relays. After the professional matches concluded, amateurs from across the region participated. Tickets were priced cheaply at 35 cents for general admission up to $1.10 for grand stand seats. In addition to the races, visitors were usually treated to musical entertainment between the professional and amateur events.

The Cyclodrome was built strategically on the Providence/Pawtucket city line. There fans could reach the site by either city’s transit lines. There was also a fair amount of parking. In 1925, when the stadium was built, such considerations had only recently become something developers had to plan for.

Cycling seems to have enjoyed a large and fervent audience in the Providence area. For the city’s 250th anniversary in 1886, the Rhode Island chapter of the League of American Wheelmen staged a parade of 1500 cyclists through the streets of Providence. Although nationally interest in cycling peaked in the 1890s, most cities and many colleges still sponsored a team. Providence not only attracted competitive racers from around the nation and in Europe, but also produced several local stars. One of these was Vincent Madonna, who placed fourth on Opening Night’s main event, the 30-mile race. Madonna was one of several Italian-Americans from either Providence or Pawtucket to race at the Cyclodrome. From the names found in several programs at the Rhode Island Historical Society and in newspaper reports, anywhere from one half to two-thirds of Cyclodrome riders were of Italian descent. Laudati, the developer, was himself born in Sicily. The city’s large Italian American community may have accounted for the success of the Cyclodrome as a racing venue.

While cycling may have been popular with the city’s newer immigrants, the other sport that really packed in audiences was football. College football had long been a popular entertainment for the region; even Brown’s often-dismal team drew fans. Laudati, however, seems to have perceived the potential of the sport to draw wider audiences and to turn a profit on the growing interest in the sport. The Providence Steam Roller is remembered today as the first professional football team in New England; it was started in 1916. Some sources contend that it was the first team anywhere to pay its players enough to be considered fully professional, at least during the season. In 1925, the fledgling National Football League granted franchise status to the Steam Roller, and thus was begun a seven-year partnership between the team and the Cyclodrome.

Adapting the Cyclodrome for football engendered some very unusual playing circumstances. The 100-yard field just fit inside the track, but there was not enough room for the now-familiar 10-yard end zones. Each end zone was cut off by the steeply banked portions of the track at the turns. Thus, one end zone was 10 yards, but the other was only five. Games were regularly packed; Providence set an early NFL attendance record of 13,000 fans for a game against the New York Giants. However, even capacity crowds of 10,000 meant that fans sat so close to the field that players who were chased out of bounds might end up in the laps of the crowd. One source suggested that the ardent Steam Roller supporters were responsible for their fair share of injuries to the unlucky opponents. Even under these difficult circumstances, however, the Cyclodrome was a major improvement from the team’s former home, Melrose Park. There the field covered the site of a former file factory, and the metal shards still in the ground notoriously were more injurious than play itself.

Another distinctive feature of the stadium is that there were no visiting locker rooms and the home team had to use the small space where cyclists changed. This space amounted to the size of two phone booths. Players took turns changing in the cramped quarters; Dick Reynolds, in his history of the team noted that the space, built to serve “small wiry chaps,” was hardly conducive to the ungainly physiques of the football players. Jim Conzelman, the coach, joked that the team sustained more injuries getting dressed than they did on the field. Although less than ideal, the home team certainly had an advantage over their opponents. There was no visitors’ locker room at all, and traveling teams were expected to change at their hotels.

The Providence Steam Roller drew large crowds throughout the 1920s. Among Peter Laudati’s personal papers deposited at the Rhode Island Historical Society are early receipts from 1928 and minutes of NFL team owners’ meetings in Chicago. For one November 18 game, Laudati took in $12,126.33 at the gate, paid $189 for newspaper advertising, $37 for bill posting, and $4518.97 to the opposing Philadelphia Yellow Jackets. After players’ salaries were paid, Laudati netted $3,891.71. At another game on November 25, Laudati sold 11,987 tickets and made a profit of $4,647.49. Laudati was doing so well that in the worst years of the depression, Laudati was described as a millionaire in newspaper accounts.

The team split its time between two Providence-area parks for a few years until it moved permanently to the Cyclodrome. In 1928, the team became the last team not currently in the NFL to win a championship. One of the team’s most famous firsts was playing a night game; to help players the ball was even painted white. However, this game was played at Providence’s Kinsley Park. Still, the success of this experiment led Laudati to install the permanent floodlights at the Cyclodrome in 1930.

Today the Cyclodrome is remembered as the home of the team; though this memory may be fading, the memory of Kinsley Park is even dimmer. It seems that despite the drawbacks for players, the stadium was an exceptionally good facility for fans. There were reportedly no bad seats in the ‘Drome, and the tight circumstances ensured that everyone was close to the action. Half-time entertainment included performances by Happy Stanley, nicknamed “Mr. Banjo,” and billed as the “Number 1 entertainer in the state.” It is not clear whether Stanley was black or a white man dressed in blackface, but he was called the “Roller’s Minstrel Boy,” in a 1956 article describing the team. Such entertainment was still a popular form of entertainment in the 1920s and 1930s, especially for urban, immigrant, and working-class patrons; minstrelsy at the Cyclodrome is one indicator of the type of crowd who attended games and races. Stanley’s most popular song was the local hit written by Don Jackson, called “Roll, Steam Roller, Roll”:

(Slowly) Steam Roller… Roll, Roll, Roll (Faster)

Across their… Goal, Goal, Goal

For while the band is playin’, stands are swayin’

Fans are sayin’ ‘ROLL, Steam Roller’

Through their line

Around to the end! That’s fine

And, now to swell the score, one TD more

So… Roll! Roll! Roll!

As the score “swelled,” so can one imagine the sound of the crowd singing along to cheer their team.

The irregularities of the Cyclodrome recall a time in professional football before the game had been completely standardized. In fact, reading such early stories reminds one of turn-of-the-century baseball, when managers and owners hustled players around the country, trying to extract whatever profit they could. How else can one account for the hurried scheduling of four games in six days? While baseball seems to have retained a fondness for its idiosyncratic parks, football fields are now completely regularized. Stories of the Cyclodrome bring the game’s earlier fast-and-loose ways alive. At that time, the future of professional football was not assured; many thought it could never match the intensity and spirit of the college game. Laudati’s scrapbook is full of clippings of columnists who argued in favor of pro football by pointing to the level of play and rambunctious crowds in Providence. Boston writers John J. Hallahan and Neal O’Hara even suggested that Hub city residents escape the dismal play of local teams Harvard and Boston College by taking the short trip down to Providence. O’Hara even predicted that in the future, college football would exist merely as a training ground for future professionals.

Also similar to baseball, in the early days of professional football there were a whole range of professional and semi-pro teams that competed against each other and against special “all-star” teams composed from college players. In 1932, the last season the Steam Roller played, such matches increased. This is probably a factor of the Great Depression, which has caused many professional teams to fold and managers to seek opponents from beyond New England. In November of that year, the Steam Roller played a “colored” team drawn from historically black colleges and universities in the South. This contest was billed as quite the spectacle for fans.

The Great Depression took a great toll on the city as a whole; such changes were not without effect on the fortunes of the Cyclodrome. The Steam Roller folded in 1932, although clippings in Laudati’s scrapbook indicate that bike and foot races continued at the ‘Drome for several more years. Laudati, however, was the consummate businessman. As enthusiasm for the sport waned, so too, it seems, did his interest in the stadium. In 1937 the site was razed and Laudati built one of the nation’s first drive-in movie theaters. Ads for the 500-car E.M. Loew’s Theater billed its location on North Main as “the cite of the Cyclodrome,” invoking the mental map of the city’s residents. It also retained its lucrative site between Pawtucket and Providence. Once again, Laudati proved himself a savvy businessman, able to read the recreational tastes of his city.

Today, virtually no memory of the original Cyclodrome exists. Photos of the site, the teams who played there, or the fans who attended events are scant. In 1977, probably shortly after Laudati’s death, the drive-in was torn down and a shopping plaza was built. Tracing the fortunes of the property itself tells one a lot about how the city fared and the entertainment choices of the twentieth century. Resurrecting Providence’s sporting past, recalling a scrappier but prideful era when the city boasted a thriving professional, semi-pro, and amateur cycling, baseball, hockey, and football scene, promises to delight today’s sports enthusiasts and civic boosters.

Sources:

- “First Cyclodrome Race Card To-Night: Opening of New Arena on North Main Street Expected to Attract Large Crowd: Lighting Effects Perfect: Programme will be Headed by 30-Mile Motorpaced Race Featuring American Champion, Verkeyn, Piscione, and Keenan,” Providence Journal, 29 May 1925, p. 8.

- “Cyclodrome Ready for Opening Meet: Well-Balanced Programme to Be Run Off at Show Scheduled for To-night: 30-Mile Race Heads List: Gastman, Madonna, Verkeyn, and Corry will Furnish Competition. Special Sprint Match Attracting Interest — Amateurs to Ride,” Providence Journal, 2 June 1925.

- “Cyclodrome Opening Attracts 9000 Crowd: Verkeyn Wins Main Event of 30 Miles: Belgian Leads from Start to Finish in Grind Behind Motors — Gastman Makes Hit — Meyer Captures Sprint Match,” Providence Journal, 3 June 1925, p. 7.

- “Mayors of the City of Providence,” from ProvidenceRI: City Government, www.providenceri.com/history/ProvidenceCityHall/mayors6.html, accessed on 11 December 2007.

- “Peter Laudati dies; was sports promoter,” Providence Journal Evening Edition, 15 September 1977, p. C-2.

- “First Cyclodrome Race Card To-Night”, 29 May 1925.

- Reynolds, Dick, The Steam Roller Story, Self-Published in Providence, 1989, in Rhode Island Historical Society collection.

- From receipts found among Peter Laudati’s personal papers, deposited at the Rhode Island Historical Society, MSS 532.

- Quoted in a 1956 special pull-out section on the Providence Steam Roller from the Providence Journal; found in Peter Laudati’s “Scrapbook of Providence Steam Roller Club,” deposited at the Rhode Island Historical Society, Oversize GV 956.P7 L37.

- O’Hara, Neal, “Telling the World,” from a 1931 column found in Laudati’s scrapbook at RIHS.

- “Notes,” Providence Journal, 8 November 1932, p. 10.

- “E.M. Lowe’s Drive-In Theater Advertisement,” Providence Journal, 21 July 1937, p. 12.

Correction/Retraction

A previous version of this article used a photo of the Cranston Open-Air Cycledrome in 1919, located at 721 Reservoir Avenue, by mistake. Similar, but not the Providence Cycledrome. We regret the error but thank Dash Bicycle Shop for the correction. The photo can be seen on the Providence Journal’s Facebook page in a post from 2012.